Characteristic (algebra)

In mathematics, the characteristic of a ring R, often denoted char(R), is defined to be the smallest number of times one must use the ring's multiplicative identity element (1) in a sum to get the additive identity element (0); the ring is said to have characteristic zero if this repeated sum never reaches the additive identity.

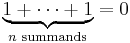

That is, char(R) is the smallest positive number n such that

if such a number n exists, and 0 otherwise.

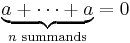

The characteristic may also be taken to be the exponent of the ring's additive group, that is, the smallest positive n such that

for every element a of the ring (again, if n exists; otherwise zero). Some authors do not include the multiplicative identity element in their requirements for a ring (see ring), and this definition is suitable for that convention; otherwise the two definitions are easily seen to be equivalent due to the distributive law in rings.

Other equivalent definitions include taking the characteristic to be the natural number n such that nZ is the kernel of a ring homomorphism from Z to R, or such that R contains a subring isomorphic to the factor ring Z/nZ, which would be the image of that homomorphism. The requirements of ring homomorphisms are such that there can be only one homomorphism from the ring of integers to any ring; in the language of category theory, Z is an initial object of the category of rings. Again this follows the convention that a ring has a multiplicative identity element (which is preserved by ring homomorphisms).

Contents |

Case of rings

If R and S are rings and there exists a ring homomorphism R → S, then the characteristic of S divides the characteristic of R. This can sometimes be used to exclude the possibility of certain ring homomorphisms. The only ring with characteristic 1 is the trivial ring which has only a single element 0=1. If a non-trivial ring R does not have any zero divisors, then its characteristic is either 0 or prime. In particular, this applies to all fields, to all integral domains, and to all division rings. Any ring of characteristic 0 is infinite.

The ring Z/nZ of integers modulo n has characteristic n. If R is a subring of S, then R and S have the same characteristic. For instance, if q(X) is a prime polynomial with coefficients in the field Z/pZ where p is prime, then the factor ring (Z/pZ)[X]/(q(X)) is a field of characteristic p. Since the complex numbers contain the rationals, their characteristic is 0.

If a commutative ring R has prime characteristic p, then we have (x + y)p = xp + yp for all elements x and y in R – the "freshman's dream" holds for power p.

The map

- f(x) = xp

then defines a ring homomorphism

- R → R.

It is called the Frobenius homomorphism. If R is an integral domain it is injective.

Case of fields

As mentioned above, the characteristic of any field is either 0 or a prime number.

For any field F, there is a minimal subfield, namely the prime field, the smallest subfield containing 1F. It is isomorphic either to the rational number field Q, or a finite field of prime order, Fp; the structure of the prime field and the characteristic each determine the other. Fields of characteristic zero have the most familiar properties; for practical purposes they resemble subfields of the complex numbers (unless they have very large cardinality, that is; in fact, any field of characteristic zero and cardinality at most continuum is isomorphic to a subfield of complex numbers). The p-adic fields are characteristic zero fields, much applied in number theory, that are constructed from rings of characteristic pk, as k → ∞.

For any ordered field (for example, the rationals or the reals) the characteristic is 0. The finite field GF(pn) has characteristic p. There exist infinite fields of prime characteristic. For example, the field of all rational functions over Z/pZ is one such. The algebraic closure of Z/pZ is another example.

The size of any finite ring of prime characteristic p is a power of p. Since in that case it must contain Z/pZ it must also be a vector space over that field and from linear algebra we know that the sizes of finite vector spaces over finite fields are a power of the size of the field. This also shows that the size of any finite vector space is a prime power. (It is a vector space over a finite field, which we have shown to be of size pn. So its size is (pn)m = pnm.)

See also

References

- Neal H. McCoy (1964, 1973) The Theory of Rings, Chelsea Publishing, page 4.